Ever wonder what happens to that balloon that slipped from your fingers as a kid? What goes up must come down. This particular happy birthday balloon was found 30 km from the closest town, but it probably came from much further away. It wasn’t Matt’s birthday, but it did bring some much needed entertainment to the day!

Author: Reid Graham

Glacial Lakes around Lesser Slave Lake

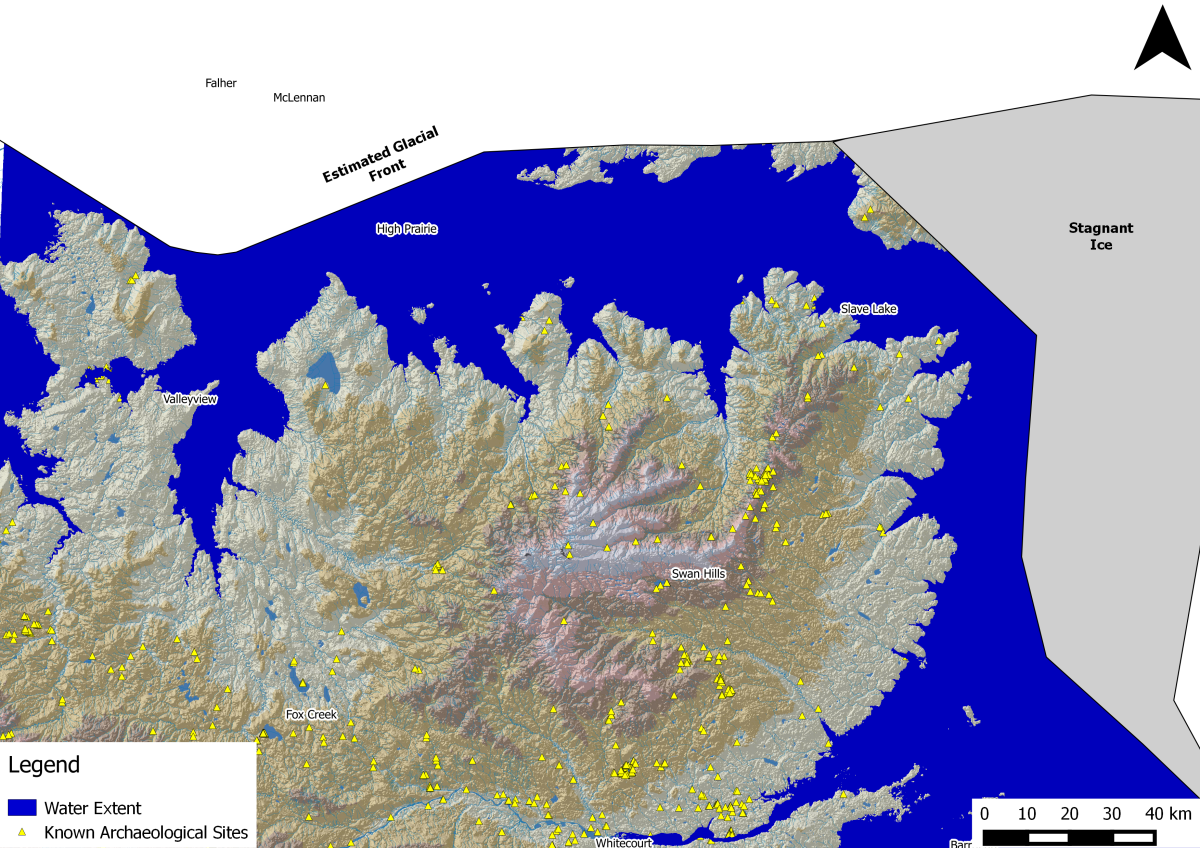

Where we find archaeological sites in the province is often strongly tied to the physical environment. We look for the different physical characteristics such as distance to water and if an area is high and dry. These features are indicators, which tell us that there could be an archaeological site in the area. This approach to finding archaeological sites is useful, but there are problems when we start considering how the landscape might change over time. The top of a hill set really far from a stream today, might have been beach front property in the past.

This is important in regards to our work on the shores of Lesser Slave Lake in Alberta. The Lesser Slave Lake basin has undergone extensive changes over the past 13,000 years, largely due to the retreating front of the glacial ice sheets at the end of the last ice age, and the incision and creation of the modern river valleys. Understanding how this environment changed over time is useful for identifying new archaeological sites in the region, as it helps us to understand how First Nations used the landscape in the past. Older archaeological sites may be on ancient beaches and meltwater channels that don’t look like they would be suitable for a campsite today, but were actually prime real estate 10, 000 years ago. These sites could be missed during an archaeological review and survey based on the modern landscape, so it is important that we understand how an area has changed, so that we can better predict where archaeological sites are going to be.

From the Shores of Lesser Slave Lake

Over the past few weeks, we’ve seen a lot of rain hit areas of the province. During this time of year, the hot humid weather generates plenty of late afternoon thunderstorms. These storms can blow in quickly with heavy rain, leaving you drenched to the bone. Just one of the many fun challenges of working in the forests of Alberta. It does lead to great photo opportunities like this one. This photo was taken on the north shores of Lesser Slave Lake, while a intense storm was sweeping through the south shores of the lake.

Slave Lake

Check out Brian Leslie looking very thoughtful near Slave Lake, Alberta

Bone Needle

This week we showcase a very unique artifact, a bone needle. This tool is very long and thick compared to the modern steel needles that we are more familiar with, but it still very sharp at the tip. The eye of the needle is diamond-shaped and tapered, which shows us that the eye was made by gouging the bone with a stone flake, rather than using a bow drill. A bow drill would have left a round hole rather than a diamond-shaped one. This type of artifact is extremely rare in North America, especially one that is complete. Most of the time when they are found, bone needles like these are broken around the eye, or you just find the tip of the needle.

This artifact was found in a dry cave in Utah, which is filled with artifacts left behind from thousands of years of indigenous people living in the cave. These repeated occupations left behind countless layers of juniper bark, which was laid down as a floor matting. The bone needle was found three meters below the modern surface. Talk about finding a needle in a haystack!

Stone Drill

This week, we showcase a stone drill. That’s right, you guessed it, this type of stone tool is used to drill holes in things. Like knives and projectile points, drills are worked on both sides to create sharp edges and a narrow tip. Unlike other stone tools however, drills are very narrow and thick, and often are diamond shaped in cross-section. This design makes the drill stronger, and less likely to break. In Alberta, stone drills are often either long and straight, with a bulb or a “T” shaped base. More often than not, you find the broken end of drills, because they snapped off while in use. The stone drill bit would be attached to a long wood handle using sinew, rawhide, and pitch, and then spun to create the circular motion for drilling. This could be either done by hand, or using a small bow and string to spin the drill.

We found this stone drill while working for Sundre Forest Products in 2012, in the Foothills west of Red Deer. The artifact is made from a brownish-gray chalcedony, and also shows evidence that it was heat treated. The drill has small “potlid” fractures, where irregular pieces of the stone popped off. This type of break happens when a stone is quickly heated and cooled.

Radial Biface

Today’s picture comes from the Ahai Mneh site on the shores of Lake Wabamun, west of Edmonton, AB. This archaeological site has a long history of human occupation, from earliest hints of people in Alberta using Clovis technology, right up to the Late Precontact and Historic Periods. Featured here is a large radial biface, made of a fine-grained siltstone. This artifact was found in a field adjacent to the site, having been turned up by a plow. While not exclusive, radial bifaces such as this one are commonly associated with the Clovis tool kit, dating back to 13 000 years ago in Alberta.

Biface from Slave Lake

This week we feature a picture of a biface found near Slave Lake, AB, a common stone tool in Alberta. The term biface is a generic stone tool classification, and simply refers to any thin piece of worked stone that has been flintknapped on both sides, or faces, of the artifact. So it can include tools like knives, arrowheads, and spear points, and certain types of cores. This biface is made of a fine-grained quartzite, and has been extensively worked around the margin to create a sharp cutting edge. The artifact exhibits a waxy luster, or sheen, that may indicate that it was heated to improve the quality of the raw material. Similar bifaces have been found in the foothills region and argued to be diagnostic of, or firmly associated with, the early middle period (5000 to 7500 BP) and referred to as Embarras Bipoints (Jason Roe, 2009, “Making and Understanding Embarras Bipoints: The Replication and Operational Sequencing of a Newly Defined Stone Tool from the Eastern Slopes of Alberta”).

Relict Shoreline Identification using Lidar in the Lesser Slave Lake Region

I’ve submitted a poster for the upcoming CAA conference in Whitehorse, Yukon in May. Check out my abstract and check back for research updates on our blog!

Advances in remote sensing technologies and industry-driven initiatives have precipitated the wide scale production of lidar-derived digital elevation datasets in Alberta. These high-precision terrain models have been instrumental for cultural resource management strategies and the identification of new archaeological sites in the province. Lidar has proven to be extremely useful in targeting of distinct landforms and topographic features present on the landscape, and in the development of archaeological predictive models. While most lidar analyses for archaeological site predictions are focused on the modern landscape, these datasets can also be used to identify ancient landforms that may have been more suitable for human habitation in the distant past. Review of lidar data from the Lesser Slave Lake region in northern Alberta revealed numerous strandlines, meltwater channels, and relict beaches related to changing levels of proglacial lakes in the lake basin. These previously unmapped topographic features reveal a fluctuating landscape during the early period of human occupation in the province, and provide an opportunity to identify potential locations of ancient sites around the Lesser Slave Lake basin. A combination of reconstructions of proglacial lake levels using strandline elevations and current predictive modeling techniques was used to identify locations reflective of this past landscape with high archaeological potential for sites. This information will be used to direct future surveys in the region, to identify archaeological sites that might otherwise have been missed by cultural resource management programs.

Scottsbluff Point

Today’s picture comes from the Ahai Mneh site on the shores of Lake Wabamun, west of Edmonton, AB. This archaeological site has a long history of human occupation, from earliest hints of people in Alberta using Clovis technology, right up to the Late Precontact and Historic Periods. Featured here is a Scottsbluff point, made of classic Alberta quartzite. This projectile point type is part of the Cody Complex, which was present across North America between 9 000 and 7 000 years ago. Point such as this one are famously associated with large communal kills, where the hunters dispatched dozens of giant Ice Age bison in natural and built traps.