Books and movies, like The Dig (author John Preston and director Simon Stone), reintroduce us to people in our archaeological history that have either been forgotten or downplayed by societal norms of the time. They encourage us to dig into the past to discover who these people were, and how they contributed to the advancement of our field. Cecily Margaret Guido, or Peggy Piggott, as she was known at the time of the Sutton Hoo excavations in 1939, was in the right place at the right time. She discovered the first item of the large collection of artifacts from the famous ship burial. But this was was such a small snippet of a long and productive career. Peggy was a very busy woman!

Margaret Guido (b. August 5, 1912, d. September 8, 1994) was an English archaeologist known for methods, field-leading research into prehistoric settlements, burial traditions, and artifact studies. Her career spanned sixty years, and was defined by high field standards, and rapid, high-quality publications. At the time of the Sutton Hoo discovery in 1939, she was already an accomplished archaeologist with plenty of fieldwork experience, and not as inexperienced or “bumbling” as portrayed in the The Dig. In 1933 she excavated under the tutelage of Mortimer and Tessa Verney Wheeler, at the Roman town, Verulamium (Hertfordshire, England). In 1934 she earned a “diploma” from the University of Cambridge, as they did not award degrees to women at the time. By 1936, she had completed a post-graduate diploma from the Institute of Archaeology in London, where she focused on Western European Prehistory. In 1937, at the age of 25, she directed an excavation at the Latch Farm (Hampshire) Middle Bronze Age barrow and urnfield cemetery, wrote up the excavation of an Early Iron Age site at Southcote (Berkshire), and published a study on the pottery from Iron Age Theale. In 1938-39 she worked on research excavations at the Early Iron Age site of Little Woodbury (Wiltshire), and published the results of work conducted at the Early Iron Age site at Langton Matravers (Dorset).

In July 1939, Guido and her then husband, Stuart Piggott, arrived at the Sutton Hoo location to aid Charles Phillips, who had assumed control of the excavations under the British Museum, the Office of Works, Cambridge University, Ipswich Museum, and the Suffolk Institute. On July 21, not long after her arrival at site, Guido had discovered the first of 263 items that confirmed the ship was a burial mound, and that the Anglo-Saxon Dark Ages were in fact a rich cultural period.

Over the next two decades, Guido’s work forged her into one of the most important British prehistorians. She conducted extensive excavations at six hillforts, excavated for the Ministry of Works during WWII, and produced approximately fifty publications for British Prehistory which advanced the fields of Bronze Age burial traditions, Late Bronze Age artifact studies, Later Bronze Age and Iron Age settlement studies (especially roundhouse architecture and hillfort chronologies). Later in her career she produced the definitive texts on Prehistoric, Roman, and Anglo-Saxon glass beads that are still used today. By the age of 32 she was elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London due to her contributions to the study of British prehistory. In 1987 she was President of the Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, a position she held until her death at the age of 82.

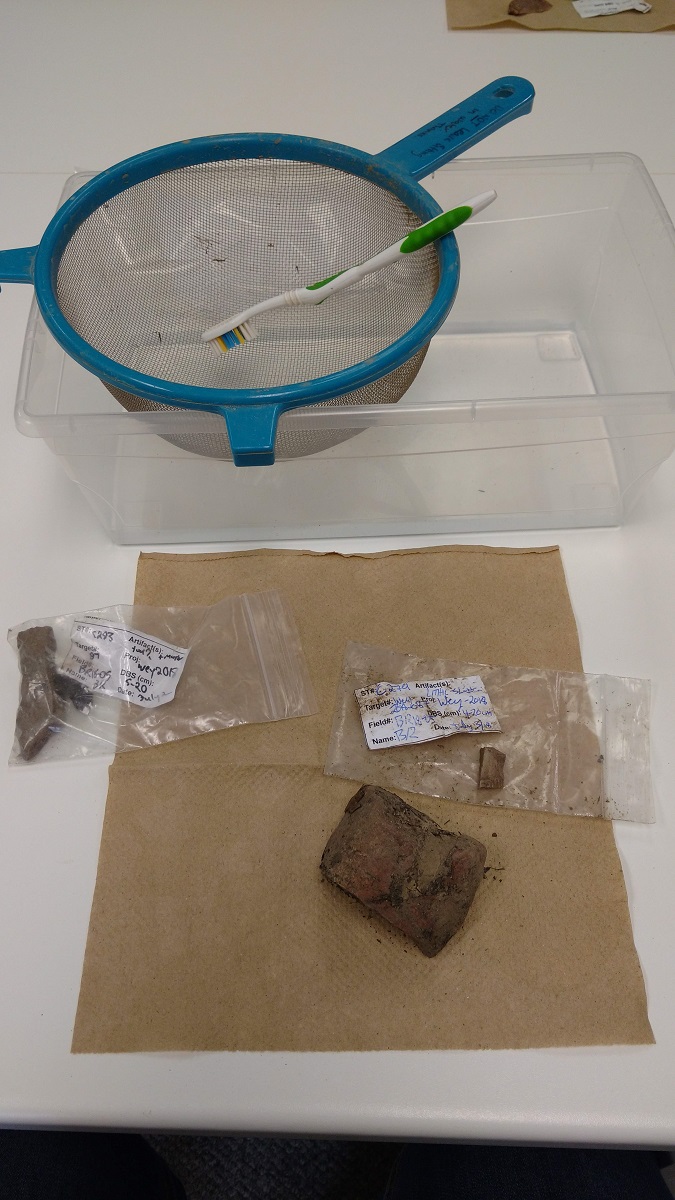

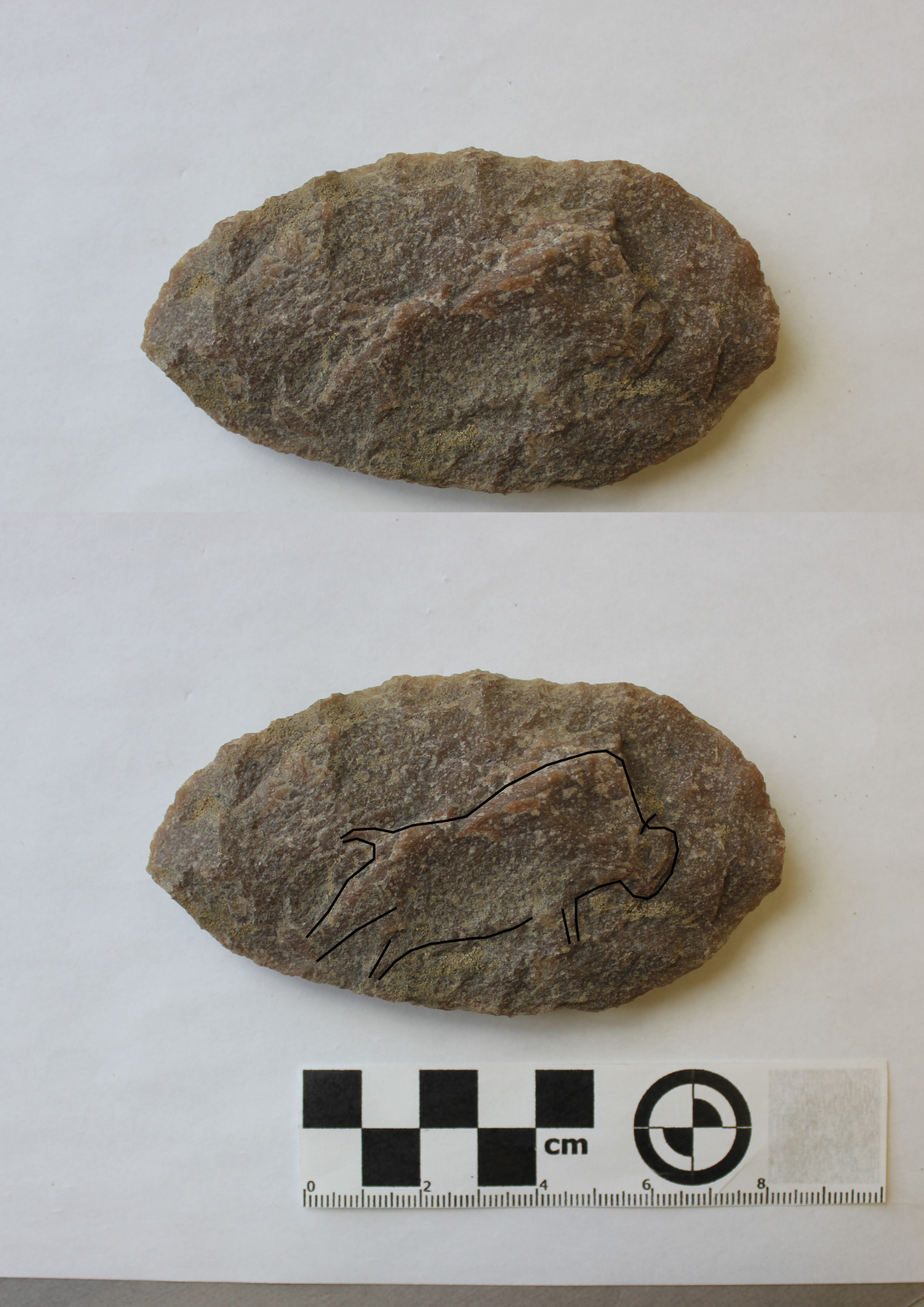

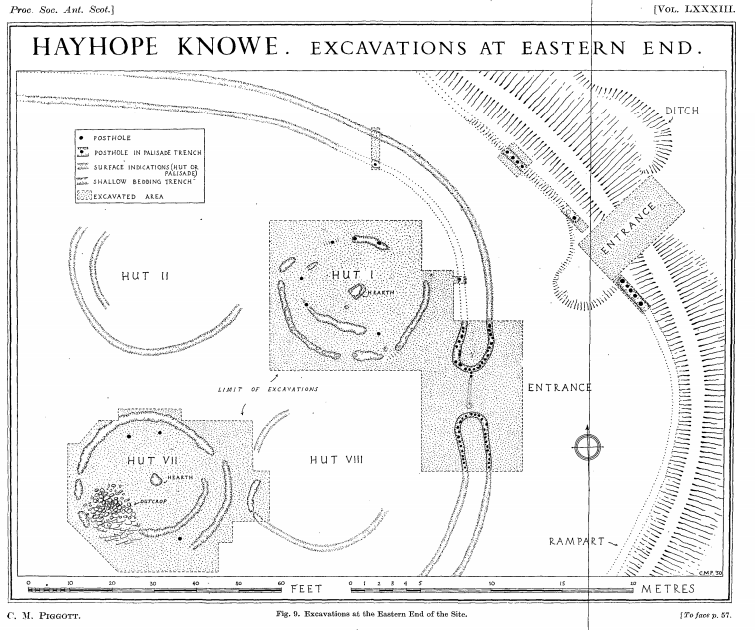

Her work on hillfort studies (both field methods and interpretations) are some of the most influential work on the understanding of early British prehistory. In 1948 she excavated Hownam Rings, Hayhope Knowe in 1949, and Bonchester Hill in 1950, and published the results within the same year. The field methods she used at Hayhope Knowe was a combination of the best parts of the Wheeler and Bersu schools of excavation, but modified to allow for quick assessment. This was the first time these were used on northern Iron age sites. As a result, in one season Guido was able to open 520 sq. m in targeted open-area trenches, which were used to investigate three houses and their enclosure sequence.

Hownam Rings became the type-site for hillfort development, known as the Hownam Paradigm. The paradigm indicated that the progressing complexity of enclosures (pallisade to multivallate earthworks) also represented complexity of cultural development. This paradigm remains valid to this day. Guido also used this site to discuss for the first time the problems of archaeological survival, slope erosion, and the vestigial nature of timber features. She also tested and refined the CBA model, allowing her to provide a relative chronological framework for later prehistoric settlement in southern Scotland. This was a major leap for prehistoric studies in the days before the use of radiocarbon dating became prevalent.

In the later part of her career in the 70s and 80s, Guido focused on researching ancient British glass beads. Her first volume covered both prehistoric and Roman period beads, and the second volume (published posthumously by Martin Welch in 1999) on Anglo-Saxon beads. She co-founded the Bead Study Trust (in 1981), and the Peggy Guido Fund for research on beads. Both volumes remain the primary reference works on the topic.

If you want to read more about the works of Margaret Guido, check out the following links!

https://peoplepill.com/people/margaret-guido/

https://trowelblazers.com/raising-horizons-queens-of-the-castles/