When bone is burnt by a fire it can undergo a range of changes in appearances, such as calcining. Calcining, characterized by its bright white colour, is caused when bone is burnt at a higher temperatures. The bone can shrink, become more white or chalky in appearance, more fragile and more likely to fragment into smaller pieces. These pieces of calcined bone were collected during the summer of 2017. Calcined bone indicates the presence of a hearth at the site.

Tag: bone

Public Archaeology at the Brazeau Reservoir

Public archaeological programs are an excellent opportunity for people with a general interest in archaeology or amateur archaeologists to learn what an artifact is, and to practice the techniques that are used to find and interpret them. Often these programs will have a dig component, where people join for a few days or a week, and learn excavation techniques in units laid out over a buried site.

The Brazeau Archaeological Project (BAP), sponsored in part by Tree Time Services Inc., provides a unique experience. The current sites being surveyed are almost entirely exposed by the continuously fluctuating water levels of the reservoir. This also means that the entire history of the area has been deflated to one level, rather than multiple occupation levels that can be apparent in excavations. The occupation of the Brazeau River by First Nations extends as far back as 12- 14,000 years ago. This allows participants to gain a better feel of how large and spread out an archaeological site can really be. The largest site surveyed so far spans almost 1 km!

The project invites members of the Strathcona Archaeological Society (SAS) to come out for a day or weekend to learn survey and excavation techniques, as directed by experienced or professional archaeologists. As most of the artifacts lay exposed on the surface due to the ever changing water levels of the reservoir, the experience is relaxed, family friendly, and can be conducted over a single day or weekend, rather than a week-long commitment.

Participants learn what features to look for when looking for surface finds, such as material, shape, and modifications. By pairing participants up with experienced archaeologists we can point out the various ways an artifact, such a flake, can look; particularly how it can blend in or really stand out from its surrounding environment. For example, Amandah van Merlin, one of the co-ordinators, picked up a small, indistinct black pebble. The black pebble chert material, however, is a popular flint knapping material. As it turned out, Amandah had found a thumbnail scraper!

Public archaeology programs are also a great way to explore new technology or try experiments. One participant brought his drone. He was able to take photos from a bird’s-eye view of the site, providing a totally new perspective on what these landforms look like along the shore, and the distances between the sites. Madeline Coleman, the other co-ordinator, laid out various sizes of brick pieces in order to examine how artifacts are affected by water movement (or perhaps even people).

The project is still in its infancy. The pilot survey in May 2015 occurred over one day and had 9 participants. In May 2016, the survey occurred over two days with over thirty participants joining for one or both days. This past May, there were over 20 participants that joined for the full weekend. In addition, for two days prior to the public survey, BAP worked with University of Alberta field school students. Here they practiced map making, shovel testing, and laying out excavation units.

Outreach is also a very important aspect of a public program, such to First Nations group, schools, and universities. The BAP has recently reached out to Paul First Nation, in whose traditional territory the Brazeau River lies, and whom are active in working to protect their heritage. BAP has also recently partnered with Katie Biittner at Grant MacEwan University to begin a hands-on catalogue experience for university students at Grant MacEwan and the University of Alberta. In addition, the original finders of the site, Sandy and Tom Erikson, worked to create a 3-case display at their hometown school in Edson. The case shows some of the finds and information from the periods they may have originated in.

Animal Bones

During an archaeological survey or excavation when animals bones are found, we look for signs that they were somehow modified or processed by humans. Animals were not only a source for food, but their skin, fur, and bones had many other uses. We might find cut marks from a knife made during butchering, or the bone itself might be shaped into a tool such as an awl. If the animal seems to have been killed or somehow used by humans we can classify it as an artifact.

However, not every animal bone that we find is an artifact. Sometimes during a survey, a test pit might have an animal bone in it. If no other artifacts were found in the area and the bone shows no signs of human use, then we cannot call it an artifact. Nature does takes its course without human interference. The animal remains pictured here serve as a reminder of that. These remains, likely of a wolf, found in the summer of 2014 will eventually be buried over time.

The One That Got Away

In this blog series, we will be reviewing and summarizing recent archaeological research occurring in the province and around the world. To see the original article, and others like it check out the Blue Book Series presented by the Archaeological Survey of Alberta.

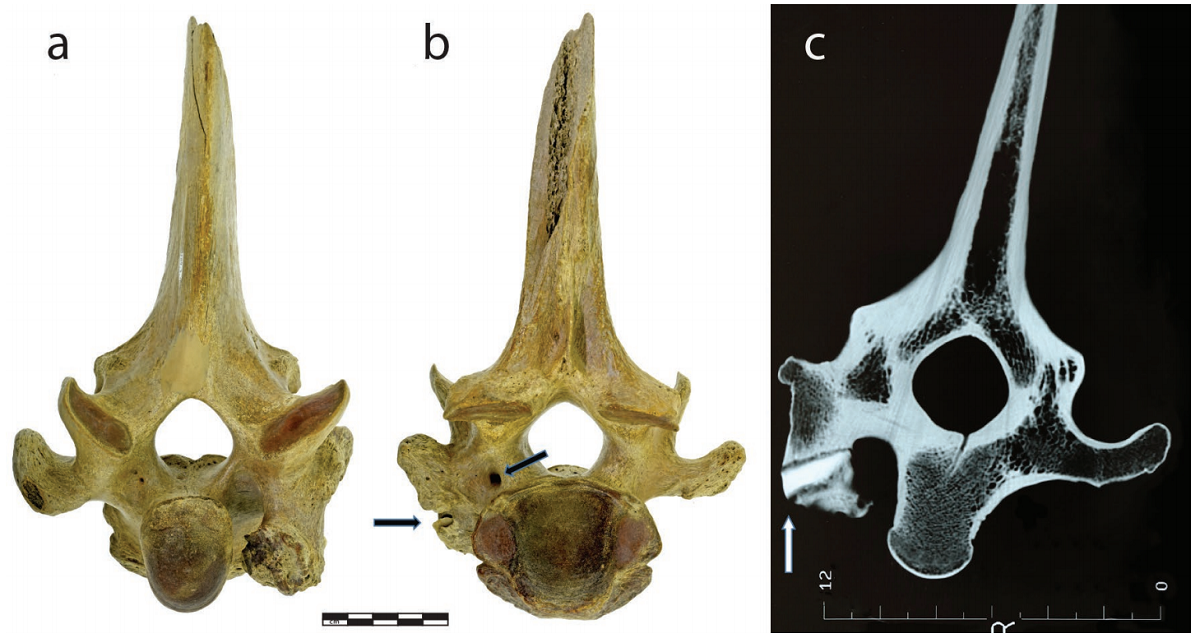

When we find animal bone in an archaeological site, we can usually tell whether that animal died of natural causes, or if they were hunted and butchered by people. Evidence of butchery is sometimes obvious. We can see cut marks on the bone that are left behind when a sharp metal or stone knife cut into the outer layer of tissue that makes up bone. We can also see different fracture patterns in how the bone breaks. You can butcher an animal with an axe, leaving behind deep gouges in the bones, or using a saw which leaves distinct striations in the cuts.

Telling how an animal was hunted is more difficult. We often have to infer how the animal died based on the surrounding evidence. If we are looking a site like Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump, we can make a pretty good guess that the animals died from falling off the cliff. If we find a bison skeleton surrounded by stone arrowheads, it likely was shot using a bow. Very rarely do we ever see “the smoking gun” in archaeology. However, in the case of the Pibroch Vertebra we have a unique specimen that provides an insight into how people were hunting in the past. In an article published in the Archaeological Survey of Alberta Occasional Paper Series, Dr. Jack Ives at the University of Alberta and Bob Dawe at the Royal Alberta Museum reviewed their findings from the Pibroch Vertebra.

Bison Jaw and Horse Tooth

At our Archaeological Roadshow event in Lac La Biche, AB Allan and Juanita Gaudreault brought in a collection of fossils. The fossils were fragments of a darkly stained bison jaw and a set of blueish grey horse teeth. Mr. Gaudreault told us the specimens were found in a low area near a lake. We came up with two possible interpretations of these specimens: they may have been permineralized due to being in a place with very hard groundwater; or could be dated to the early Holocene.

It is quite rare to find animal remains in the boreal forest in central and northern Alberta. The acidic soils of the boreal forest make for very poor preservation conditions. Animal bone is therefore rare, and these finds could help teach us about past environments in the region.

Tree Time Services reached out to Chris Jass, Curator of Quaternary Palaeontology at the Royal Alberta Museum (RAM), for more information on determining a possible age for the specimens. Jass confirms that “you can get fairly dark staining and mineralization fairly quickly depending on the depositional environment. However, if there’s a horse there, (the Gaudreaults) may be finding some older material.” Horses were native to North America, but went extinct sometime between 13,000 and 11,000 years ago (North American horse teeth were also recently found at the Brazeau Archaeological Survey project ). The horses that are ubiquitous in North America today were introduced by the Spanish in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. Due to the fossilized nature of the specimen and the recovery of the teeth from a possible relic lake bed, these horse teeth may be from the extinct North American horse.

Chris Jass goes on to state that he has “been working with a diver who has been pulling bones out of Cold Lake, and we’ve got Pleistocene dates (>11,700 years ago) on a bison that he’s recovered from the lake. I think there is considerable potential for recovery of late Pleistocene/early Holocene (ca. 11,700 years ago) material in many of the lakes in Alberta.”

On September 7, 2016 Corey Cookson, Project Archaeologist at Tree Time Services, and Christina Barron-Ortiz, Assistant Curator at the Royal Alberta Museum, made the trip up to the Gaudreault’s home to view the rest of their collection. Christina Barron-Ortiz is a specialist in horse and bison teeth. She confirmed that the horse tooth has the characteristics of several specimens the Royal Alberta Museum recovered from the lake bed near Cold Lake, AB. She also suspected that the bison jaw bone represented ancient bison but could not be as sure as the horse. With permission from the Gaudreaults, the bison jaw and horse tooth were collected and results from carbon dating are expected in the Spring.

Bone Needle

This week we showcase a very unique artifact, a bone needle. This tool is very long and thick compared to the modern steel needles that we are more familiar with, but it still very sharp at the tip. The eye of the needle is diamond-shaped and tapered, which shows us that the eye was made by gouging the bone with a stone flake, rather than using a bow drill. A bow drill would have left a round hole rather than a diamond-shaped one. This type of artifact is extremely rare in North America, especially one that is complete. Most of the time when they are found, bone needles like these are broken around the eye, or you just find the tip of the needle.

This artifact was found in a dry cave in Utah, which is filled with artifacts left behind from thousands of years of indigenous people living in the cave. These repeated occupations left behind countless layers of juniper bark, which was laid down as a floor matting. The bone needle was found three meters below the modern surface. Talk about finding a needle in a haystack!