Have you been to Maligne Lake? If so, you’ve seen some of Mary Schäffer’s work, for her survey of Maligne Lake was used when the area was incorporated into the Jasper National Park.

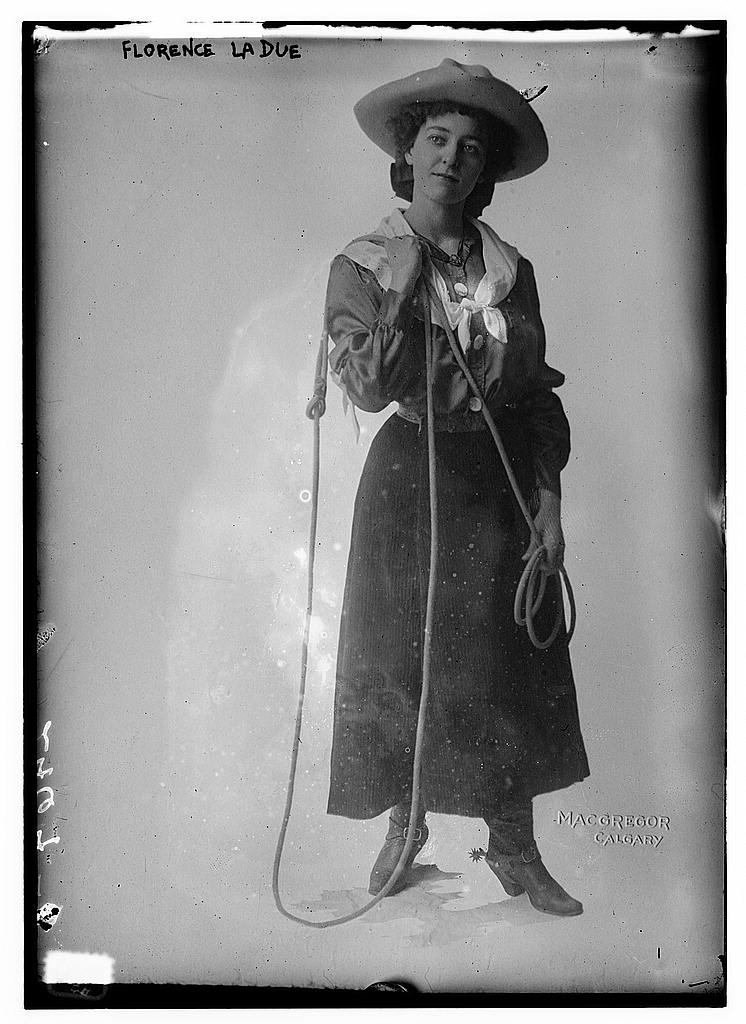

In 1911, Mary was asked to survey Maligne Lake by the Geographical Board and Geological Survey of Canada. This was incredibly unusual as Mary wasn’t a trained surveyor and government policy at the time prevented women from accompanying survey parties, let alone leading one.i However, Mary’s position was unique; she and her friend Mollie Adams had been the first non-Aboriginal women to see the lake and had already completed several exploratory expeditions in the Rockies by the time of the government’s request.

An American by birth, Mary got her start in the Rockies after she and her husband took a rail trip to the west in 1889. Afterwards, the couple decided to spend their summers undertaking botanical studies in the Canadian Rockies. Mary’s husband, Charles, suffered poor health and this kept them close to the railway line for their research. After Charles’ death in 1903, Mary began to travel further into the Rockies in order to complete the illustrations for the guidebook she and her husband had planned on creating. Along the way, she got much help from guides, outfitters, and Aboriginal people and developed friendships there. By the time she finished collecting specimens in 1906, she was hooked on exploration.

Mary had developed a friendship with a geography teacher from New York named Mollie Adams. The women spent two summers exploring the valleys and lakes north of Lake Louise. The goal of their 1907 expedition was to explore the headwaters of the Saskatchewan and Athabasca Rivers, but they were also hoping to find a hidden lake known only to the local Stoney Nakoda First Nations and called Chaba Imne (beaver lake).ii Mary and Mollie had no luck in locating the lake that year, but when they were returning to the railway at the end of their field season, they met a group of local First Nations people and joined them for dinner at the cabin of Elliot Barnes in the Saskatchewan River Valley. One of the men recalled visiting Chaba Imne with his father around 20 years earlier. This man’s name was Samson (also written Sampson) Beaver and from his decades old memories he was able to draw Mary a map outlining the route. The following year, Mary was able to use the map to make her way to the lake, which she named Maligne Lake.

Mary wrote about her 1907 and 1908 expeditions in Old Indian Trails of the Canadian Rockies. This is her most famous book. It is an important work because it contributed to the protection of the Maligne Lake area through raising its public profile, but it’s also important because it reflects the social standards of the time and part of what life was like for women and First Nations in Canada at that time. For example, it wasn’t proper for women to be leading such adventurous and dangerous expeditions, especially with men who were not their direct relatives, and so you’ll see that very little is said of her male guides and companions, especially in comparison to her horses. The book also illustrates the colonial practice of changing Indigenous place names and the idea that areas already known to local people were “discovered” by Euro-Canadians.

Mary took many photographs during her explorations. Many can be found at the Whyte Museum in Banff. Here you can see photos Mary took and hand-coloured of Sampson Beaver and his family, nature scenes, and shots of the expedition, as well as some of her possessions.

The site was identified when we were surveying a disturbed area. Like Corey explained in

The site was identified when we were surveying a disturbed area. Like Corey explained in