As Consulting Archaeologists, most of our work supports “regulatory compliance”. We help developers get government approval by assessing and mitigating potential impacts to historic resource sites. I’m frequently asked by developers whether a specific project requires Historical Resource Act Approval (or “Clearance”, as it was known before 2012).

This isn’t as easy a question as one might think. Different projects have different levels of impact, and not every development requires approval. Guidelines for developers are spread across numerous Bulletins and buried in the Instructions for Use of the Listing of Historic Resources. To make life easier, I thought I’d try to summarize these rules in one place. Please keep in mind that HRA regulations are constantly changing, so this is a snapshot of the state of the system in spring 2020. If you know of another trigger, or a development class I’ve missed, please let me know.

Alberta Culture uses a variety of triggering mechanisms. The key tool for determining HRA Requirements is the Listing of Historic Resources. The Listing was originally developed as a screening tool for small-scale oil and gas. In response to requests from industry and regulatory agencies to provide more transparency and certainty, Culture is moving towards using the Listing for a wider range of developments.

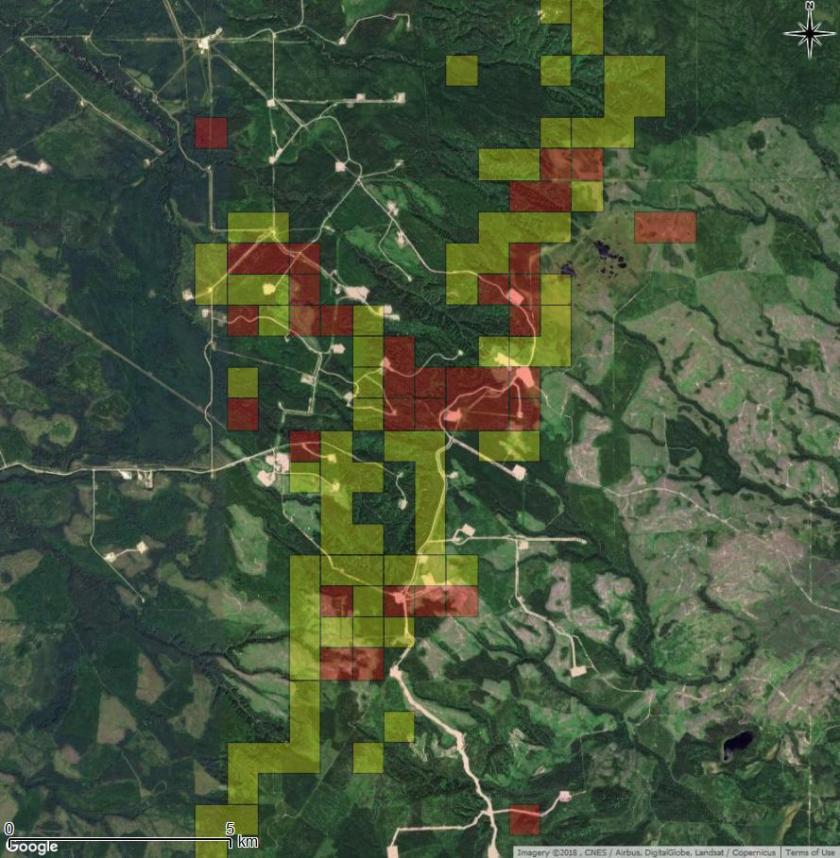

Parcels of land are registered on the Listing with a Historic Resource Value (HRV). HRVs are ranked from 1 through 4 for known sites, or 5 for lands believed to contain a site (high potential). Each entry on the Listing also has a class, which represents the type of resource. Historic resources can include archaeological sites, paleontological sites, Traditional Land Use Areas, and historic buildings. (You can read more about different types of resources here). There are still many areas of Alberta that have historic resources potential that are not included in the Listing. This is only one of of the many tools used during the screening process.

According to the Listing Instructions, there are several types of development that always require an application for HRA Approval:

- Any project that requires an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA): These applications generally result in a requirement for a Historical Resources Baseline Assessment.

- Any project that requires National Energy Board (NEB) or Alberta Utilities Commission (AUC) Approval

- Forest Harvest Plans: These can be managed through the special Forestry HRA Compliance process. This is Tree Time’s specialty. Contact me before submitting an Application in OPAC.

- Class 1 Pipelines

- Projects requiring Conservation and Reclamation Approval by Alberta Environment. According to the Conservation and Reclamation Guidelines for Alberta this includes:

- The construction, operation or reclamation of a well, battery, oil production site, pipeline, transmission line, telecommunication system, mine, pit quarry, peat operation or plant.

- The conduct or reclamation of an exploration operation for coal or oil sands;

- The construction or reclamation of a roadway

- The reclamation of a railway

- All Area Structure Plans and other long-term municipal planning documents.

Some development types use the Listing to selectively trigger requirements for HRA Approval:

- Small-scale conventional oil and gas developments (wellsites, pipelines, access roads, etc)

- HRA Approval is required if the footprint overlaps any HRV Listed lands.

- Surface Materials (sand, gravel, clay, peat, etc. pits):

- 5 ha or larger / Class 1 Pits: HRA Approval is always required.

- Under 5 ha / Class 2 Pits: HRA Approval is required if the project area overlaps HRV 1, 2, 3 or 4 lands (known sites).

- Subdivisions:

- Most subdivisions: HRA Approval required if the project area overlaps any Listed lands (HRV 1-5).

- Simple subdivisions (first parcel out, 80-acre split, lot / line boundary adjustment or parcel consolidation): HRA Approval required if the project area overlaps HRV 1, 2, 3, or 4 lands (known sites), but not HRV 5 (high potential).

- Oil Sands and Coal Exploration operations (drilling programs and associated clearing, access and reclamation): HRA Approval required if the project footprint overlaps any Listed Lands (HRV 1-5).

- Geophysical Programs (seismic): HRA Approval Required if the project footprint overlaps HRV 1, 2, 3 or 4, (known sites) but not HRV 5 (high potential).

- Geotechnical exploration operations(drilling programs, including those in support of other projects). HRA Approval Required if the project footprint overlaps HRV 1, 2, 3 or 4, (known sites) but not HRV 5 (high potential).

- Pipeline Integrity Digs (and similar operations, including all access, workspace, laydown, etc). HRA Approval Required if:

- The activities will extend off the original disposition footprint, and overlap any Listed lands (HRV 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5), or

- Any activities are on HRV 1, 2, 3, or 4C lands, even if they’re limited to the existing footprint.

- Utility Distribution Services (including power, low pressure gas, and water supply projects that aren’t triggered by the EIA, NEB, or AUC processes): HRA Approval Required if:

- The project footprint overlaps HRV 1, 2, 3, or 4 lands (known sites), or

- The project footprint overlaps HRV 5 lands (high potential) and involves trenching on undisturbed land (eg. native prairie or forest).

Several other Regulatory processes trigger a review of the Listing and fall under the general Instructions for use of the Listing:

“In the absence of a Land Use Procedures Bulletin specific to the proposed project type and/or industry, the proponent must submit a Historic Resources (HR) Application”

- Public Lands Dispositions:

- the LAT (Landscape Analysis Tool) reviews all applications against the Listing and notes a Condition (2060) requiring HRA Approval for any dispositions in HRV 1, 2, 3, or 4 lands (known sites).

- Dispositions not covered by the Bulletins above, such as miscellaneous leases (MLL), and licenses of occupation (LOC) may also be referred for HRA Approval for HRV 5 lands by approvals officers.

- Water Act Applications: the Wetland Application Checklist requires submission of the results of a Historical Resources Act “Search”. Any developments that involve significant ground disturbance and overlap Listed lands (HRV 1-5) should be submitted for HRA Approval.

- Temporary Field Authorization: The TFA Application form requires applicants to check the Listing and requires HRA Approval for all Listed lands (HRV 1-5).

- Biophysical Impact Assessments: Some municipalities (eg. Calgary) include a check of the Listing, or a requirement for HRA Approval, as part of a Biophysical Impact Assessment.

Generally speaking, any development or activity should be referred to Alberta Culture for HRA Approval if it is:

- Located in Listed lands (HRV 1-5), and

- Involves disturbance of native prairie or forest, or deep excavation

If you don’t know where to start, or would like someone to review your project before you submit it to Culture, contact me (Kurt) or one of the team at 780-472-8878 or toll free at 1-866-873-3846. You can also email us at archaeology@treetime.ca. We’re happy to help!