We are heading into the fall of 2020 and the season crunch is in full swing! We have been pretty busy, despite the challenges of COVID-19, and have found quite a few new and exciting sites. This makes us recall the sites of 2019! It was hard to make time to write up what we found in 2019. Although we find over 100 sites every year, these sites stand out either because we found interesting artifacts or the site is unique in some way.

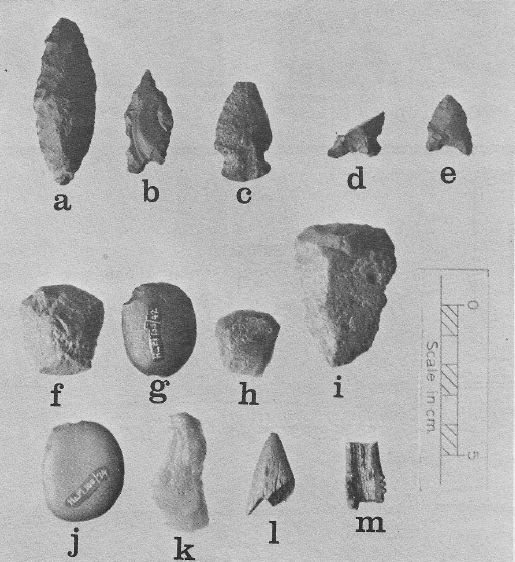

GgPs-6: Found while assessing a proposed cutblock for Vanderwell Contractors near Swan Hills, AB. The site is located on an irregular ridge surrounded by muskeg and set back from a small lake. At this site we found an asymmetrical projectile point made of quartzite. The projectile point doesn’t fit any of the established diagnostic styles known in Alberta, but could possibly be a hafted knife similar to this knife we found back in 2014.

FgPw-21: Found while assessing a proposed cutblock for Weyerhaeuser Pembina Timberlands near the Brazeau Reservoir. The site is located on prominent hill surrounded by muskeg. At this site we found a small biface made of purple quartzite and a utilized Knife River Flint flake. The biface appears to have been resharpened in the past and was likely once much larger. The tool was likely discarded once the flintknapper felt the tool became exhausted and unusable. The flake of Knife River Flint, is an exotic material that comes from a source in the Dakotas. Along the sharp edges of the flake, small chips we call utilization scars or wear was observed. Sometimes all a person needs is a sharp flake to get the job done!

GgPs-10: Found while assessing a proposed cutblock for Vanderwell Contractors near Swan Hills, AB. The site is located on an irregular knoll overlooking muskeg to the south. Usually we find 1-10 flakes in shovel test, which we interpret as hitting the periphery of a flintknapping scatter likely associated with a single tool production event. Sometimes we get a positive test with 30-50 flakes in a shovel test and feel we hit the knapping area dead-on. If multiple lithic materials are present it likely represents various tool production events. But at this site we hit a full-on lithic workshop! We recovered four hammerstones, five cores, and a total of 7888 flakes!

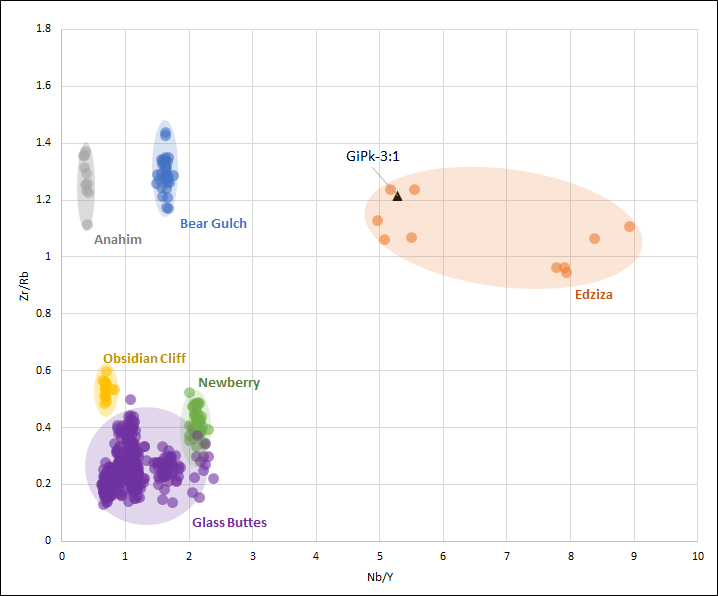

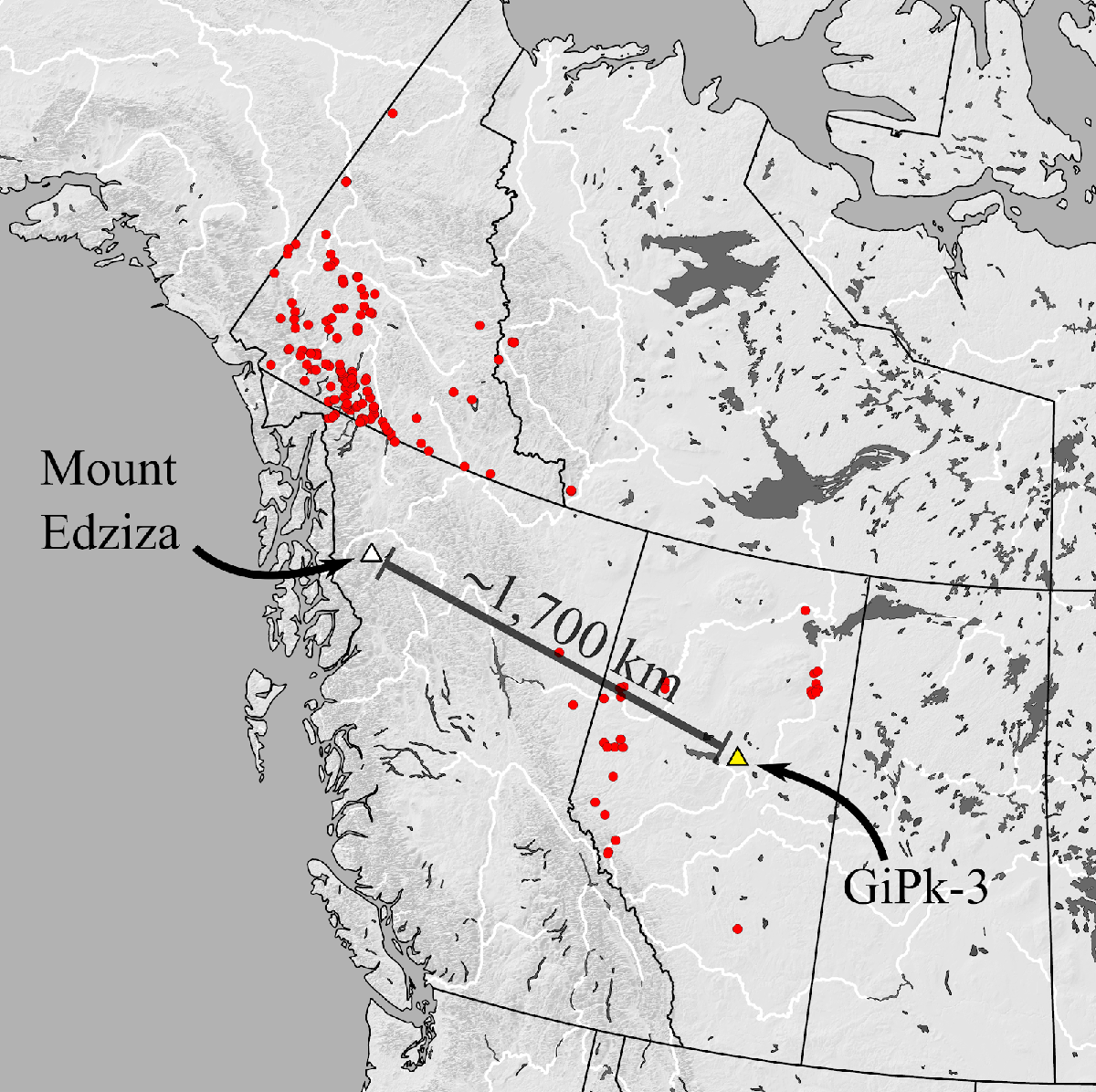

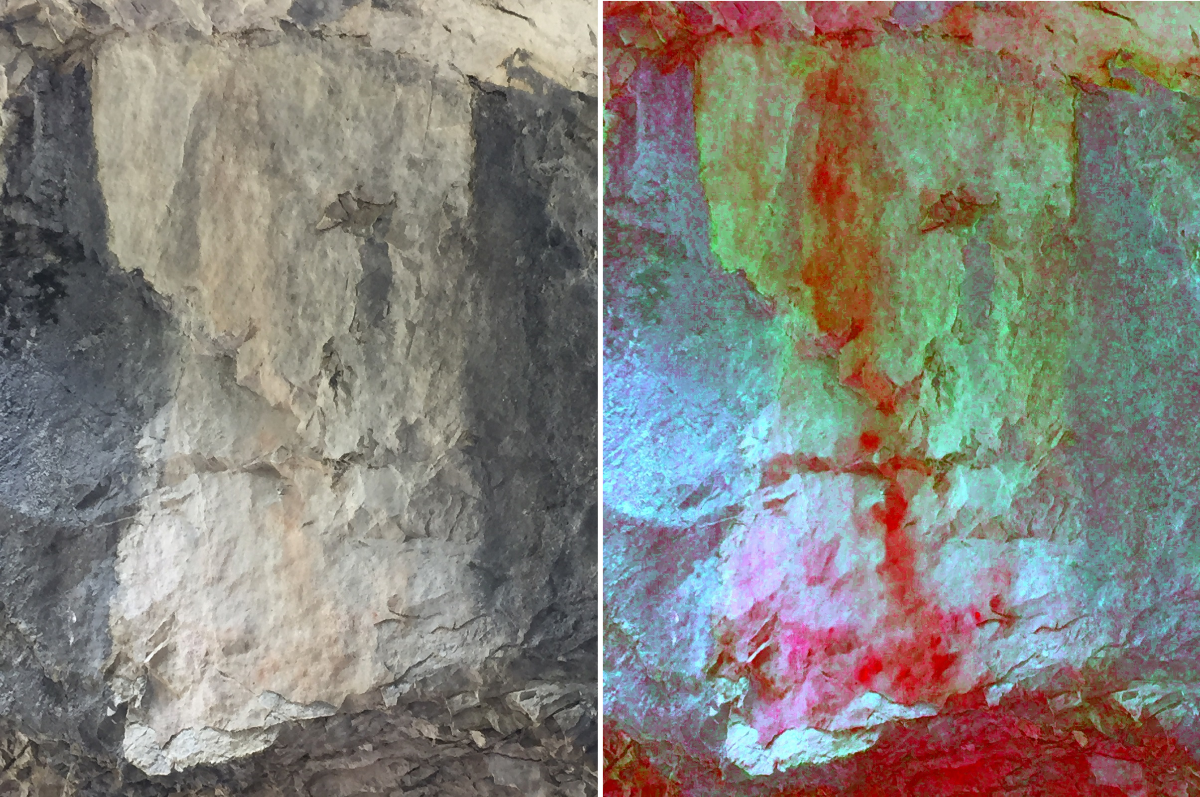

GiPk-3: Found while assessing a proposed cutblock for Vanderwell Contractors near the Fawcett River. The site is located on a small knoll located southwest of the river and overlooking a wetland to the south. Although we only found one artifact at this site, it is a very interesting tool. The tool is a portion of an obsidian flake made using microblade core technology. The blade has some utilization wear along the lateral edges, as indicated in the picture above. As we have discussed before, obsidian is a volcanic glass and each volcano has a unique chemical signature that allows us to trace where the artifact material came from. We were able to zap this specimen with the pXRF and discovered this obsidian came from over 1700 km from Mount Edziza in British Columbia!

FiPx-5: Found while assessing a proposed cutblock for Blue Ridge Lumber near Niton Junction, AB. The site is located on a long ridge that comes to a high point in the southeast. At this site we found a 90 m long site with flakes, cores, and one ugly projectile point. The projectile point might represent an aborted point that the flintknapper discarded. One of the lateral edges and the one of the notches are broken off, which may represent an error during tool production which resulted in the tool being discarded.

FiPx-2: Found while assessing a proposed cutblock for Blue Ridge Lumber near Niton Junction, AB. At this site we found lithic debitage, two cores and one bone awl. The bone awl is somewhat degraded and the point is not very sharp, but it appears to have been sharpened into a point at one end. The awl would have been used to pierce and mark materials such as leather and wood.

GdPu-19: Found while assessing a proposed cutblock for Blue Ridge Lumber near Swan Hills, AB. The site is located on a low southeast facing edge overlooking a relict oxbow. Although we didn’t find much lithic debitage at this site, we found two hearths (old campfires), 54 pieces of faunal remains (animal bones), and lots of charcoal. Two of the animal bones have indicators of human modification in the form of cutmarks, polish, and spiral fractures. The charcoal from both hearths and the calcined bone were all sent away for radiocarbon testing and received dates of: Charcoal Calibrated AD (1495-1650 AD); calcined bone Calibrated AD (1681-1937 AD). While not very old, this site is interesting in that it was occupied just prior to European Contact in Alberta!

FcPx-39: Found while assessing a proposed cutblock for Sundre Forest Products near Nordegg, AB. The site is located on a west-facing terrace overlooking Dutch Creek. At this site, we found a beautiful siltstone biface preform. Much like GiPk-3 and other sites where we only find one formed tool, these sites likely represent a tool being dropped or lost by hunter or flintknapper.

FcPx-50: Found while assessing a proposed cutblock for Sundre Forest Products near Nordegg, AB. This site is located on a series of rolling hills overlooking the North Saskatchewan River. At this site we found one biface and 15 pieces of lithic debitage. The biface is made from Red Deer Mudstone, also known as Paskapoo Chert, is a material we do not find often. Additionally, we also found one piece of obsidian which was sourced to Bear Gulch, Idaho.

FcPx-49: Found while assessing a proposed cutblock for Sundre Forest Products near Nordegg, AB. This site is located on a large prominent ridge located back from a deeply-incised stream. At this site we had 12 positive tests over 170 x 75 m area. In these positive tests, we found one siltstone biface, two cores, one animal bone, and over 1000+ flakes. Several of the flakes also showed signs of utilization wear.