Have you ever been outside enjoying nature and thought to yourself – this sure is a sweet spot! Whether you are camping, fishing, hunting, or just enjoying the outdoors, there are certain aspects of our favorite spots that make them ideal and cherished. Nice sheltered level ground near the river – great for camping and fishing. Elevated location with a 270° degree view overlooking a muskeg – great for moose hunting. It just so happens that many of the things we look for in the perfect camping or hunting spot, are also the characteristics that First Nations people were looking for throughout the many millennia that they inhabited North America.

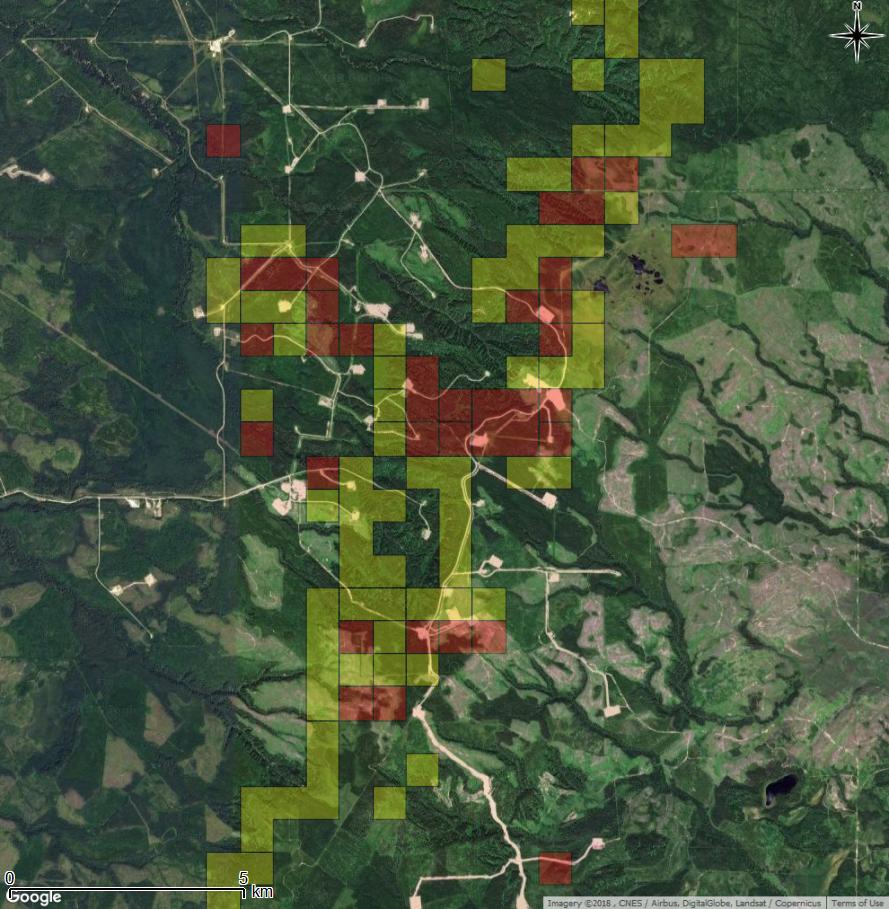

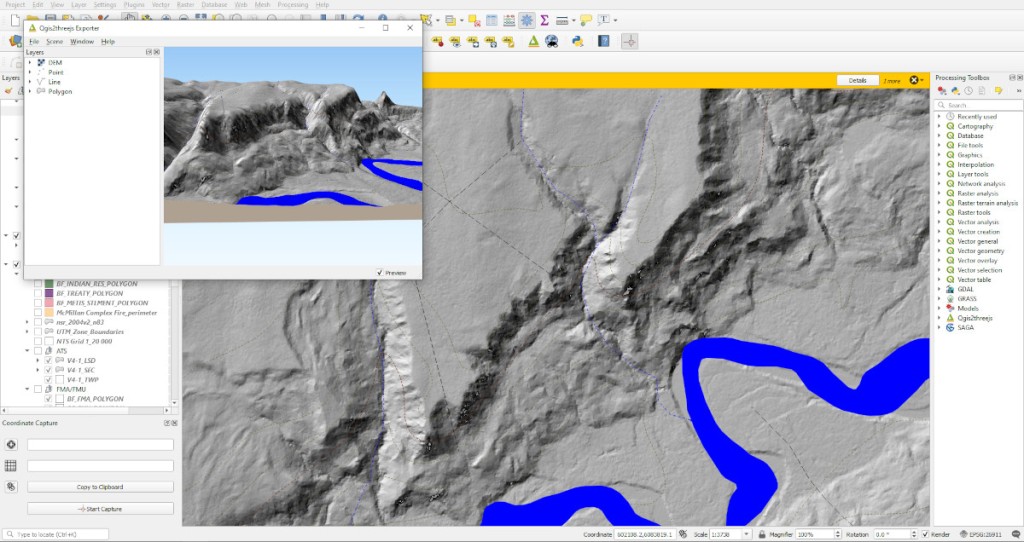

Archaeologists at Tree Time Services Inc. use high-resolution imagery, 3D and predictive modelling , as well as keen eye, when screening development footprints for our clients. However much of what we do boils down to simply trying to find good camping and resource procurement areas within the footprint. When our survey crews walk up to a targeted landform and see an ideal camp site or vantage point, usually someone will confidently declare that this is a site, or comment that ‘this is a sweet spot!’ – more often than not, they’re right!

In 2016, Kurt and I were doing some work for Alberta-Pacific Forest Industries in an area near Anzac that was affected by the Ft. McMurray wildfire. During screening, Corey had targeted a small knoll along a continuous bench with low-lying, marshy terrain to the south. Upon arriving at this location, both Kurt and I took note of the panoramic view that this little knoll offered, and it just so happens that someone else had as well. A permanent hunting stand had been erected on the knoll. Although it looked slightly aged, it was still strong and sturdy.

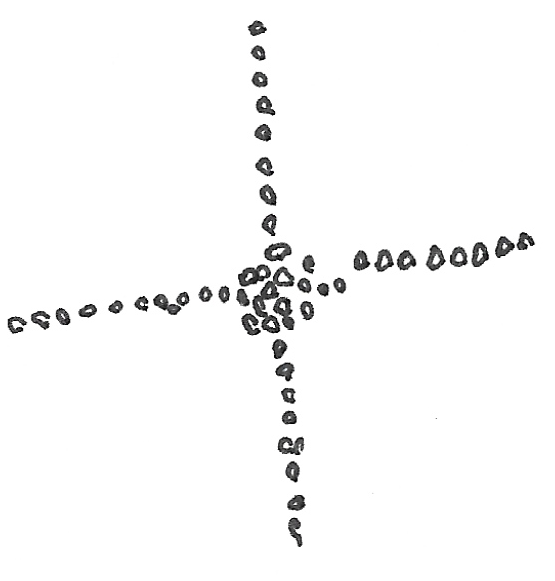

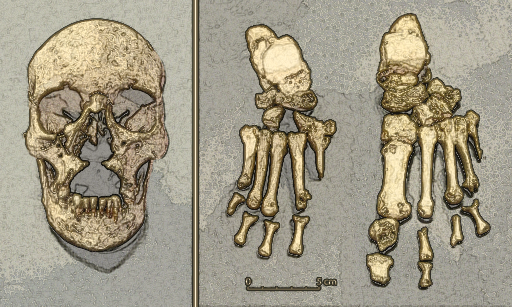

After only a couple quick shovel tests, Kurt found a single chert flake and we were able to designate the knoll as a new archaeological site. We then delineated the site (determined how big it is), but after many more tests, we had failed to recover another artifact. Somewhat disheartened that this site would only be recorded as a small, isolated find, Kurt started flagging the buffer and suggested that I continue digging some evaluative shovel tests. Digging these extra shovel tests may recover more artifacts, and add to our gathered information. I dug a couple more tests close to where Kurt found the flake with no luck.

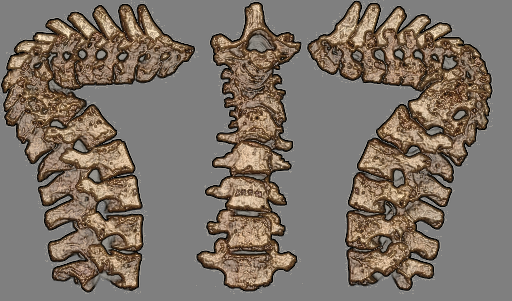

Kurt however, sometimes likes to test low-lying areas at sites, especially if they are sheltered from the wind. So on his recommendation, I put my last test in the low ground at the back of the bench. We generally focus on high, dry ground, so a low spot such as this is usually assumed to be less likely to have artifacts. After shaking through some dirt, I looked down, and to my surprise there was a projectile point in my screen! If it wasn’t for Kurt’s decision to begin site evaluation, the site would have remained a rather insignificant isolated find. In this case, a small amount of site evaluation allowed us to not only dramatically increase the site’s significance, but also gain more information concerning the site’s age and the activities that had occurred there.

The small siltstone point we recovered, is likely an atlatl dart point and is very similar to Besant-type points (2500 – 1350 years old) found on the northern plains. It is also bears similarities to points belonging to the Late Taltheilei (1300 – 200 years old) tool tradition used by caribou hunters in the Northwest Territories. More archaeological research conducted in the boreal regions of Alberta may provide us a clearer picture of the movements of people in the past, but as of now our knowledge of past cultural interactions is somewhat limited. Artifacts from sites such as this, increase our understanding of past lifeways and provide data for future research.

It is interesting to note that the tip of the dart point is missing. The tip of the point may have been accidentally broken off during its production or re-sharpening, but it could have also been broken during use. Point tips regularly break off when they hit something hard in flight, such as bone, a tree or a rock. This point missing its tip is an interesting example of the continued use of a landscape for a specific purpose.

This knoll, which is currently someone’s hunting spot, was also used for hunting over a thousand years ago. Alberta alone has over 40,000 registered archaeological sites, and this number grows every year. There is a good chance that ‘sweet spot’, which you use for camping, hunting or fishing, has been used repeatedly throughout the past and will be continued to be enjoyed by future generations. Next time you are out and about, take a minute to think about how we share the land with past peoples and how our landscape shapes the human experience. If you happen to discover archaeological material at your favorite spot, be sure to inform the Government of Alberta so that it can be properly protected for future generations!