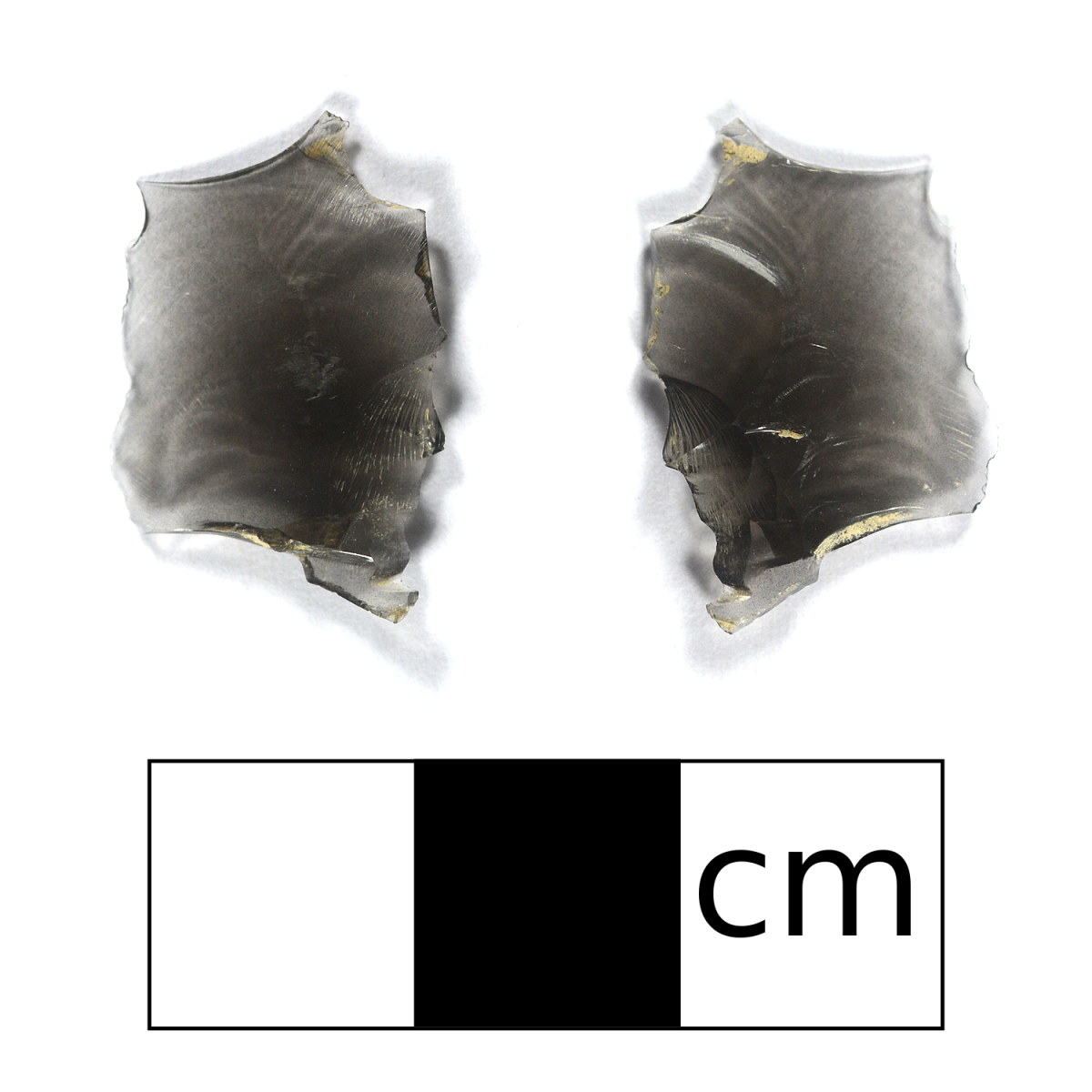

If you take a survival coarse, read outdoor living manuals like Northern Bush-craft, or talk to people who spend a great deal of time in the wilderness, one of the first items they suggest always having is a good knife. A good bush knife can be the difference between life and death in a survival scenario, much like a means of water purification and starting a fire (multiple BIC lighters is king!). When surveying the Boreal forest most of what we find are the remnants of First Nations Peoples making cutting implements out of stone. Unless you are an expert flint knapper, I would not recommend making stone tools in a survival situation and instead just follow the experts advice. However, with so many different types of knives on the market today, choosing which knife is best for you may be very daunting. So I asked the archaeological staff at Tree Time Services Inc. what type of knife they carry, why they carry that knife, and what they like/dislike about it? With this information, and my own personal experience, I wrote this guide on knives to share with our followers. Keep in mind, that not all clients allow knives on projects, so occasionally we have to leave them at home.

Folding Knives

Although I would not a consider a folding knife (a.k.a. pocket knife) the best choice for bush-craft, they do have certain qualities that make them quite useful when compared to other options. They key aspect that make folding knives a decent option is right in the name: they fold. Folding knives are the best type of knife for every day carry (EDC) because they are portable, usually lightweight, pack-able and easy to deploy like a Spyderco Paramilitary II. I would not buy a heavy or bulky folding knife. I want to put the knife in my pocket or pack and forget that it is there until I need it. I also would not buy a folding knife that cannot be operated with only one hand. Folding knife technology has advanced enough that knives that require two hands to open (or close) are now obsolete, but some people just fancy the more traditional style and aesthetic of a Buck 55 or Opinal #8. However, when buying any knife, especially folding knives, it is important to buy one that has a comfortable handle. While they may be aesthetically pleasing, many folding knives are very uncomfortable to hold and will cause hotspots and blisters during extended use.

The major downside to folding knives is that the fold is an inherent weak spot, which makes them far less durable than fixed blades, although perfectly adequate for small cutting tasks. Many people would choose lightweight and easy to carry over heavy and bulky. When doing archaeological survey, we have multiple means of communication (cellphone, radio, and In-Reach), and it is extremely unlikely that we would spend any longer than 24 hours stuck in the bush. Both Reid and Elenore think a pocket knife is perfectly adequate for what we do and don’t bother carrying a fixed blade knife. In my 10+ years of forest life, I have never been in a true survival situation, but I carry a fixed blade knife nonetheless, because I want to have it if I need it and I find it useful for tasks unsuited for a folding knife.

Fixed Blade Knives

When choosing a fixed blade over a folding knife, you need to decide whether you want portability or durability. Fixed-blade knives don’t fold, and therefore they need to be carried in a sheath on your belt or attached to a pack. While both types of knives are very proficient at cutting things (provided the edge is well maintained), fixed blade knives are much more versatile. They are universal tools that can be used for many things that would break a less durable folding knife. Digging holes, chopping down trees and cutting firewood, can all be done with a good fixed-blade knife, but would quickly destroy a folding knife. However, keep in mind that not all fixed blade knives are created equal, and a good bush-craft knife should have a full tang (the metal of the blade extends all the way to the base of the handle). This makes the knife substantially stronger than a knife that only has partial tang, or no tang at all, like those “Rambo”-style knives that have a hollow handle. Sure it may seem nice to be able to store matches and snare wire inside your knife, but that hollow-handle knife will break long before a full-tang knife will.

Before choosing which fixed-blade knife to buy, you need to decide what you will be using the knife for, and how much weight are you willing to carry? For instance, Tim carries a Gerber Vertebrae, which is small 3 inch, lightweight blade. In contrast, I carry a Ka-Bar, which is not small (7 inch blade) or lightweight, but I can use it as a small machete to clear helipads, cut roots out of test pits, and baton it through firewood with ease. However, when it comes to fine jobs requiring manual dexterity, the Gerber Vertebrae shines, while the Ka-Bar is just too big for precision cuts. Jay carries an older Gerber knife similar to the Gerber LMF-2 Infantry, which is probably a happy medium between what Tim and I carry. With a 5 inch blade, Jay’s knife is still light enough to be dexterous, while still being large enough to chop and baton.

Vince carries the now discontinued Gerber Guardian, which is a double edged knife that is extremely cool, but not the most useful for anything other than Tactical Forest Operations. Vince admits that while two edges do not dull out as fast as one, his knife cannot baton through wood and is somewhat awkward to use since you can’t put your thumb on the spine while whittling. If price is a concern, but you still would like a good fixed-blade knife then look no further than the Morakniv Companion. These knives are very durable and come highly recommended by many outdoor and survival enthusiasts. Not to mention that you could buy 10 of them for the price I paid for my Spyderco Paramilitary II! Brittany lost her Morakniv Light My Fire this year and doesn’t seem to feel too bad about it.

Multi-tools

The usefulness of multi-tools is undeniable and most of the archaeologists at Tree Time carry one into the bush. Swiss Army knives are great, but Leatherman’s addition of pliers to the “boy scout knife” in the 1980’s changed the multi-tool forever. Since then the multi-tool market has exploded and many different variations with different types of tools are produced by many different manufactures. When buying a multi-tool it is important to keep in mind that when carrying gear through the forest all day “ounces become pounds”. Like other knives, you need to balance weight with usefulness. Ask yourself “do I really need that tiny pair of scissors when I am already carrying a multi-tool with two knife blades and a fixed-blade on my belt?”. Do this for every tool, and soon you will realize that a lightweight multi-tool with 10 functions is likely better. Sure it may seem like a good idea to get the Leatherman Surge with 21 different tools, but it also weighs in at a whopping 12.5 ounces, which is nearly a pound. Luckily many multi-tool manufactures have realized that weight is a concern for many people and have designed tools, such as the Leatherman Signal, with backpacking in mind.

Personally, I would refrain from getting a micro multi-tool like the Gerber Dime or Leatherman Micra. While these are extremely lightweight, I’ve always found that the pliers just don’t generate enough force and the knives just aren’t big enough. If force generation is a must, SOG recently designed the “Power-” line of multi-tools that have a mechanism the doubles the force applied to the pliers. Another important thing to consider when buying a multi-tool is whether you can access the tools with the pliers in the closed position and whether it can be operated one-handed. Like knives, not all multi-tools are created equal and it is important to do a bit of research before you buy a product to ensure you made the right choice.

Digging Knives

While I like to carry a knife that I can use for digging if need be, Kurt likes to carry a knife that was especially designed for the task. When conducting archaeological survey, Kurt carries a folding knife, a multi-tool and a Hori Hori Knife. The Hori Hori knife is a Japanese knife that is part trowel, part knife and is traditionally used for gardening. The dished shaped knife features a serrated blade on one side and a straight blade on the other, although Kurt wishes these were reversed so that the straight blade faced down when held in the right hand. The Hori Hori knife is large enough to be used as a small machete, and is very useful for cutting sod, removing roots from test pits and troweling through tree throws. According to Kurt, the major downfall of the Hori Hori knife is that it does not have a full tang, and the blade becomes loose with heavy use. Since the handle is riveted, there is no way to tighten the handle once it slacks off. Kurt says he may replace the rivets with screws so that he can periodically tighten it up.

In the past, Kurt has also carried a Lesche knife, which is another knife designed primarily for digging and loved by the metal detector community. Although Kurt was fond of this knife, he says that he gave it up for the Hori Hori, due to the offset handle making it awkward to carry. Like trying to carry a trowel on your belt, the offset handle sticks out from your body and gets caught on branches and trees while navigating dense forests. However, he was very fond of the sheath and it fit his Hori Hori knife perfectly.

Folding Saw

I will mention one other tool that is extremely useful and hard to do without. Folding saws are an excellent tool that are a necessity for anyone doing archaeology in the Boreal forest. There have been countless times where a tree or large branch is totally blocking a cutline that we need to quad down to access our work area. Instead of walking for an extra 3 km, we simple deploy a folding saw and cut the tree out of the way. If I know there will be lots of deadfall, I bring a chainsaw, but sometimes one small tree can mean the difference between a 200 m or a 2000 m hike if you can’t get your quad around it.

The two main types of folding saws we use are the “folding” type and the “collapsible” type. Both of these saws work, but a folding saws is more portable and easy to deploy, whereas a collapsible saw is better at actual cutting. Madeline uses her Kershaw folding saw so much she actually keeps it in her vest. She uses it to clear trails and get those pesky roots out of her test pits. Last year Tree Time bought 4 of the collapsible Agawa Boreal 21 Saws for people to take with them on the quads. We found that these saws were extremely useful, and cut through fairly large trees with ease.

Closing Remarks

When purchasing knives, multi-tools or saws for work, or pleasure, remember to ask yourself “do I actually need this?”, and better yet “do I really want to carry this around all day?”. This is what you have to remember when buying a folding-knife versus a fixed-blade knife, a 7 inch blade versus a 4 inch blade, a 21 function versus 12 function multi-tool or a folding versus collapsible saw. Weight adds up very fast when you have to carry it around for 12 hrs a day, every day, so it is these small choices that make all the difference. You cannot leave your food, water, GPS or first aid kit at home, but you can choose a multi-tool that is 5 ounces lighter, or a knife that fits in your pocket. However, always remember that outdoor living is always a trade off, and conscious well thought out decisions should always guide you when choosing your kit.