The majority of Tree Time’s archaeological work is done in the context of Historic Resources Impact Assessments, but what is an Historic Resource?

People are sometimes confused about what constitutes an historic resource because it is a very broad category. The first thing to come to most people’s mind would likely be the contents of a museum but as discussed below, historic resources encompass far more than the displays at museum. In the simplest sense an historic resource is anything of significant interest to a community, a cultural group, historians, archaeologists, or other scientists.

Alberta’s Historical Resources Act defines Historic Resources as:

“any work of nature or humans that is valued for its palaeontological, archaeological, prehistoric, historic, cultural, natural, scientific or aesthetic interest.”

A Historic Resource Site is any place where Historic Resources are found. When we say “site” people most commonly think of an archaeological site, but this is only one type. Alberta Environment and Parks has defined six categories of Historic Resource sites – archaeological, cultural, geological, historic, natural and palaeontological. However, an Historic Resource site can fall into multiple categories – one doesn’t take precedence over another. Some examples of this are the Big Rock Erratic at Okotoks which is classified as both a geological and an archaeological historic resource site and the Frank Slide which is both a geological and historic site.

The government of Alberta keeps track of all the known historic resource sites in the province. To do this they use a tool called the Listing of Historic Resources. This listing is a database that contains information about historic resource sites such as their location and a description of what they are and what condition they are in. It is important to be aware that not all historic resources are recorded in this listing as many of them have not been recorded yet and the listing is not updated every day.

Some examples of Historic Resources sites found in Alberta:

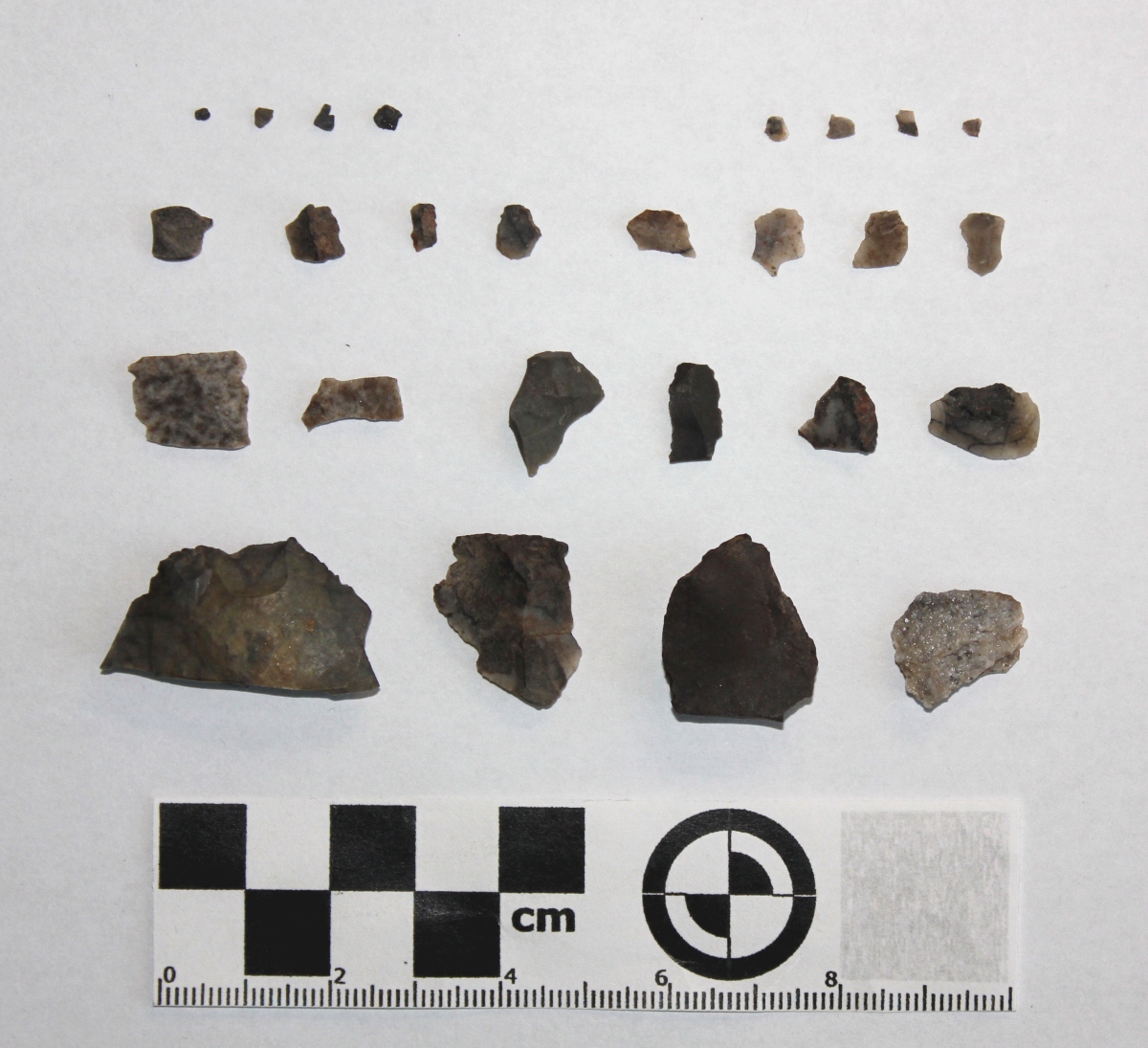

Archaeological Sites

Archaeological sites are areas that have been occupied by humans in the past and have evidence of that occupation in the form of artifacts found on or under the earth’s surface. Some examples of archaeological sites common to Alberta include precontact campsites, rock art, tipi rings, buffalo pounds, homesteads, trails and medicine wheels. Some well known examples of archaeological sites in Alberta include Head Smashed-In Buffalo Jump and the Bodo Archaeological Site.

Cultural sites

Cultural sites are sites that have been identified as significant to a specific cultural group by members of that group. These sites often include historic villages, cabins and community campsites, burials, prayer trees and other ceremonial sites. The majority of Culturally Significant sites are of First Nations origin, but not all are. Some examples are Pierre Grey’s Trading Post, the St. Charles Mission Site, the Grande Cache Dinosaur Tracks site, the Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Village and Áísínai’pi (Writing-on-Stone) rock carvings and paintings. Culturally significant historic resources often overlap with archaeological and historic period sites.

Geological sites

This site type will often have overlap with other types of Historic Resources. Geological sites are areas of the province with unique geological features like the Canmore Hoodoos, Hetherington Erratics Field and the Whitecourt / Woodlands Meteorite Impact Crater.

Historic Sites

Historic sites are places that can usually be related back to specific people or events in history. This category is a little more complicated because it includes heritage structures, historic places and districts, and historic period archaeological sites.

The most common Historic Sites are places with preserved historic buildings. The Province tracks historic buildings in a database called the Heritage Survey. Any structure older than 50 years is eligible to be added to this list. This of course includes old buildings, like houses, grain elevators and train stations, but also includes other types of man-made above-ground structures, including earthworks, preserved wagon trails, and early 20th century oil wells. Historically significant structures or places can be designated as Municipal or Provincial Heritage Resources, and protected. Some examples of these include include the Brooks Aqueduct, the Alberta Pacific Grain Elevator near Castor, the Parliament Building in Edmonton and old houses in the Highlands neighbourhood of north Edmonton.

Other Historic sites are areas with known historical significance. While these sites may not have retained any standing structures they are places where significant events are known to have taken place or important historic figures visited. These include the locations of many historic fur trade posts and forts. Some of these sites have been recreated for public enjoyment and educational purposes. Some examples of this are Fort Victoria, Lac La Biche Mission and Historic Dunvegan. Other historic sites in Alberta include the Victoria Settlement, Frog Lake Massacre Site, and the Grand Rapids Portage on the Athabasca River.

Historic period archaeological sites are the most common example of overlap between two categories. These are places with underground material evidence of the past (archaeological resources) from the historic period. At these places, archaeologists have documented the presence of historic period artifacts, ranging from fur trade beads and tools, to early 20th century cans and bottles. We may or may not have written records about these sites. Common examples of this site type are fur trading posts, pioneer homesteads, and early trapping cabin locations. A less common example would be this plane crash.

Natural sites

Natural sites are areas of special and sensitive natural landscapes of local and regional significance. These sites often have overlap with archaeological and historic site types. Some examples are Eagle Butte, Purple Springs and the Rumsey Natural area.

Palaeontological sites

These are sites where fossils can be found. Fossils of plants, animals and even dinosaur bones fall into this category. Examples include Dinosaur Provincial Park near Brooks and Pipestone Provincial Park near Grande Prairie.