Ever wanted to combine a hobby you enjoy with work you are passionate about, like scuba diving and archaeology? In 2013 Vince and I did just that. Archaeologists tend to be naturally curious people, always wondering “what’s over there?” or “what’s under that?”, so its not surprising that many archaeologists also enjoy scuba diving. There are plenty of opportunities for the public to try their hands at archaeology right here in Alberta (such as at Bodo or Brazeau) but as avid scuba divers Vince and I decided to try our hands at underwater archaeology at a more exotic location.

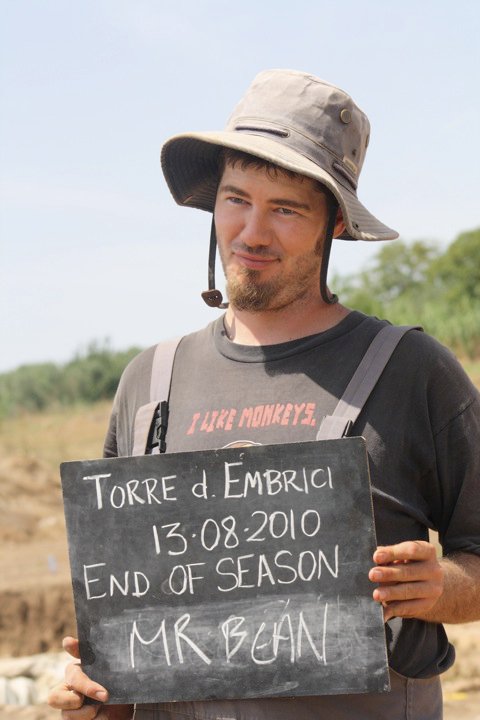

For two weeks in April-May 2013 Vince and I attended the Sanisera underwater field school at the Cap de Cavalleria on the island of Menorca, Spain. This field school was conducted by the Ecomuseum de Cap de Cavalleria (now called the Sanisera Archaeology Institute for International Field Schools). This is a large field school with something for everyone and we met people from all over the globe who shared our interest in archaeology. In addition to the underwater fieldschool, there were two other fieldschools being held on land at the same site. One excavation was taking place at the Roman city (Sanisera), and the other was at one of the seven Roman necropolises located near the city. Our group was underwater investigating shipwrecks in the harbour. The site was diverse and included not only the areas mentioned above but also a Roman military camp which predated the Roman city, a quarry and an 18th century British watch tower.

We started each morning by hopping into the van and driving to the dive site. On the beach before diving we would discuss which survey methods we were going to use that day and what our objectives would be (since we couldn’t speak once we were under). Then we would gear up and hit the water. Some days we would have to swim a fair distance before submerging and some days the sea was too stormy (or too many jellyfish) to dive at all.

Four different underwater survey strategies:

1. Snag line – two divers swim in the same direction with a weighted rope pulled tight between them dragging it along the bottom and stopping if it “snags” an object. When an object is snagged the ends of the rope are pinned to the bottom and the divers follow the rope to the object. If it is an artifact they record it, if it is something like a rock they unpin the rope and continue.

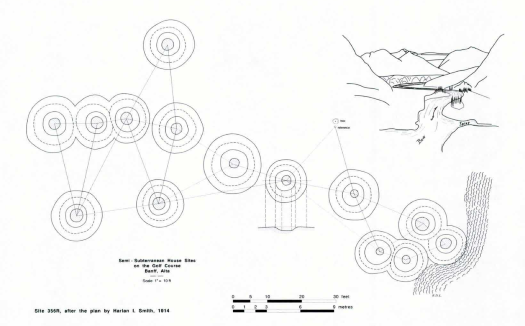

2. Circular search – to perform a circular search one end of rope is tethered to something that won’t move (a datum) then either multiple divers can space themselves out along the rope and survey a circle around the datum, or one diver can make multiple circles around the datum moving down the rope with each new circle to cover the same amount of space as the multi-diver scenario.

3. Swim-line search – a linear method, the swim-line search sees divers hold onto a rope to make sure they and maintain a consistent speed and keep their distance between each other as they move together in a line. A tug on the rope indicates that someone along the line found something and for everyone to stay put until it is recorded.

4. Jack-stay search – this type of survey is useful for carefully covering a predetermined area. Two parallel lines are fixed to the seabed (called jack-stays) and a movable rope is laid out spanning the distance between them. Divers then use the movable rope as a guide for their search starting at opposite ends, where it meets the parallel fixed jack-stay lines, and swim towards one another. When finished surveying the ground below the movable rope is adjusted along the length of the stationary jack-stays as the survey progresses slowly working from one end to the other effectively creating temporary survey corridors. When the search is midway through, the rope system will resemble a capital “H”. The two fixed jack-stay lines running parallel to each other form the vertical lines and the movable rope, perpendicular to the other two, would form the middle part of the “H”.

We practiced all of these survey techniques with the exception of the snag line and also practiced mapping artifacts underwater and taking photos. The artifacts we found were mostly amphorae that had spilled out of wrecked cargo ships, but we also found two anchors. We finished our dives around noon, got out of our gear, packed it back into the van and then returned to the Ecomuseum.

![62652_10201016614636967_11606336_n[1] - Copy](https://treetimearchaeology.files.wordpress.com/2018/04/62652_10201016614636967_11606336_n1-copy.jpg?w=840)

Once at the museum we would have a debriefing about what we found, compare our notes and maps and have a short lecture. While we were doing this the students from the terrestrial field schools were cleaning and cataloging artifacts. We didn’t collect any artifacts from our underwater survey as keeping them underwater is the best way to preserve them at present. After our short lecture we would sometimes have a longer lecture that all three field schools would attend, these lectures were useful to all the groups as they usually discussed topics such as the history of the site, findings of previous excavations or focused on specific artifact types (for example how to tell where an amphora was manufactured based on vessel shape, temper type or colour of the clay).

We had a few days that we didn’t do any diving, lectures or excavation. On those days all three field schools were taken on tours of the island to visit other archaeological sites relating to the pre-Roman inhabitants of the island – the Talaiotic. We were also taken to the island’s capital city Mahon (Maó) to visit the museum where our instructors gave talks about some of the artifacts on display and we visited the back rooms to see some unique artifacts that were not currently on display. At the end of the field school each student gave a presentation to our specific field school group and to all the instructors.

If you know anyone who is interested in giving archaeology a try it is definitely possible to get your hands dirty no matter where in the world you live. Joining your local Alberta Archaeological Society chapter is the best way to hear about great (and often free or kid friendly!) ways to get involved and to learn from the experts.